Written by: Catalina Parra Moncayo, Senior Manager, Advisor on Livelihoods, Gender, and Social Protection

How does the Graduation Approach promote labor inclusion on Colombia's Caribbean coast?

In Latin America, the lack of decent jobs remains an open wound: millions of people face structural barriers that prevent them from escaping informality.

This reality has a greater impact on women caregivers, who face lower employment rates and a high probability of remaining in the informal economy: 62% of them are in this situation (ILO, 2018), a figure that is higher than the regional average, where currently 50% of workers are in formal employment (ECLAC, 2023).

En Colombia, el 65% del tiempo laboral de las mujeres no es remunerado, y, sin embargo, su trabajo de cuidado aporta hasta el 20% del PIB nacional. A nivel regional, esta contribución asciende al 21% del PIB en América Latina (PNUD, 2024).

This finding reflects a paradox: those who sustain the well-being of society remain systematically excluded from formal employment, without social protection or stable incomes.

Confronting the structures that perpetuate labor inequality requires a deep look at the asymmetries that exist. Young women caregivers in particular face additional obstacles—from care overload to lack of certified training—that limit their access to decent jobs. A systemic approach to the labor market is needed to:

- Recognize and certify the value of caregiving knowledge.

- Strengthen technical and social-emotional skills tailored to the market.

- Promote regulatory and cultural changes to facilitate labor participation.

- Linking local capabilities with specific demands from the productive sector

Only then will it be possible to open doors and make progress in closing historical and gender gaps in areas of high socioeconomic vulnerability.

With the aim of addressing this situation, at Fundación Capital we have developed a successful initiative based on the adaptation of the Graduation approach1, a methodology recognized by academic institutions and evaluators such as J-PAL and IPA for its effectiveness in sustainably overcoming extreme poverty.

Fundación Capital redesigned it to respond to a critical challenge: the employability of women caregivers. This adaptation goes beyond traditional technical training, as it integrates:

- Women's empirical and community capabilities.

- Processes of economic empowerment and financial inclusion.

- Strengthening support networks.

- Partnerships with the private sector.

- Transformation of social norms that have relegated them to unpaid care work.

The approach does not seek only to enable women to access employment. Its goal is for them to remain and progress in the formal labor market, breaking the structural cycles of poverty and exclusion.

The background: Informal and unpaid work

In Latin America, women’s low participation in the labor market cannot be understood without addressing the structural weight of unpaid care work. According to the ILO (2024), women spend more than three times as much time on care work as men, which limits their availability to access formal and sustainable employment.

ECLAC, ILO, and OECD document a slowdown in job creation over the last decade, exacerbated by weak growth, high informality, and shocks such as the 2020 pandemic (see sources at the end of the article).

The convergence of informality, poverty, income inequality, and time use creates deep gaps between those who manage to access formal jobs and those who do not. These gaps vary according to the heterogeneity of Colombia's regions and disproportionately affect young people and women, especially those who are responsible for caregiving tasks in their homes. This calls for strategies that enable the transition from precarious contracts, unstable and informal incomes, and lack of social protection to jobs with decent pay and access to social security.

Talking about employability in the Colombian Caribbean region and some of its most important centers, such as Cartagena, Barranquilla, and Santa Marta, means recognizing a context with unique structural conditions and high potential for transformation. The Colombian Caribbean coast, with dynamic sectors such as tourism, logistics, and trade, is fertile ground for innovation with Graduation methodologies that facilitate the integration of women caregivers and young people into the formal labor market.

María became a mother at age 18 and, like millions of women in Latin America, she worked her way through informal jobs while caring for her three children. The birth of her third child led her to make a change: she decided to seek new opportunities to transform her family's future.

Through Fundación Capital's Employability and Gap Closing initiative, María discovered that the skills she acquired in caregiving and the informal economy are also valuable in the labor market. She gained confidence, learned to use digital tools, and understood that economic autonomy is key to preventing gender-based violence.

Today, she is ready to contribute to formal employment with her talent, commitment, and resilience. Her story reminds us that every female caregiver who gains access to decent employment not only changes her own life, but also boosts the local economy and breaks cycles of intergenerational exclusion.

María del Socorro O. – Participant in the initiative in Barranquilla

Why should we care about this reality?

On the Caribbean coast, there are many women ready to work; the problem is that the market does not always create inclusive spaces to hire them. Our goal is to close the gap between women's willingness to work and job openings with decent conditions.

Fundación Capital is aware that this is just one step on a path that many are already working on and contributing to, but one that requires persistence and the creation of an ecosystem that aims for structural change: from assistance to transformative inclusion, which not only improves individual lives, but also boosts the local economy and contributes to more equitable and sustainable development.

This is where this project finds its purpose: to strengthen job opportunities for the most vulnerable groups, young women and caregivers, so that they can move forward in recognizing and reaching their full economic and social potential, increase their capacity for agency, and transform the gender norms that have historically limited them.

How do we begin?

From this perspective, in 2020 Fundación Capital set out to adapt the Graduation approach for employability, building on its well-documented results and long-term effects in sustainably reducing poverty2, its capacity to adapt to different contexts3, and impacts that have been shown to last up to 10 years4. One of the most widely tested methodologies for overcoming poverty, Graduation, is thus reframed as a pathway toward formal employability.

We began with an experimental program in collaboration with Fundación Carvajal, focused on young people and implemented in a context where the consequences and restrictions of the COVID-19 pandemic were still present. Among the key elements considered in redesigning the methodology were:

- The search for cost-efficient mechanisms that reduce costs and increase the likelihood of scaling up.

- Increased involvement and retention of young people in the program, taking into account their interest in digital technology and adaptation to the context caused by COVID-19, which at that time made it difficult to implement programs in the field with face-to-face components.

- As part of the methodological adaptation process, an evidence-based strategy was developed that combined the use of surveys and a rigorous benchmarking exercise.

This approach made it possible to identify good practices and generate specific recommendations for future interventions aimed at improving access to the labor market for vulnerable young people and women. The resulting analysis provided objective inputs for adjusting the intervention approach and validating the hypotheses formulated at the beginning of the innovation process.

One of the main adjustments made to the traditional graduation approach was the transition from face-to-face mentoring to a hybrid approach with an emphasis on digital tools. A transmedia methodology was designed to increase the participation, engagement, and retention of young people, integrating educational content in multiple formats and digital platforms that are familiar and accessible to them.

The second area of transformation was the incorporation of artificial intelligence technology to expand coverage, reduce operating costs, and improve the participant experience. Solutions such as the following were integrated:

- Virtual support and training system: A learning and support environment was consolidated using smartphones as the main channel of interaction. This strategy acknowledged the high level of mobile penetration among the target population and leveraged social media and digital platforms to deliver content, microlearning modules, interactive challenges, and personalized guidance. The implementation of a transmedia approach in 2024 was envisioned as a catalyst for greater engagement and training effectiveness.

- A support system was designed using WhatsApp, complemented by a call center. This tool is not aimed at training, but rather at facilitating, in an agile and contextualized manner, the link between participants and real employment and entrepreneurship opportunities in their territory. Its purpose is to reduce friction in the job engagement process by providing personalized and relevant information in an automated but friendly manner.

This adaptive approach demonstrates the capacity of graduation methodologies to innovate and respond to employability challenges in urban contexts, leveraging technology as a key enabler. The strategy not only increases the scalability and sustainability of the approach, but also generates useful evidence for public policy decision-making and for social investors interested in cost-effective solutions with a high impact on productive inclusion.

Transitioning from informality to formality on the Colombian Caribbean Coast

The Employability and Closing Gaps Program in Colombia’s Caribbean Coast did not focus solely on placing women in jobs; rather, it sought to transform the rules of the labor market by recognizing care work as a pillar of economic and social development. The experience showed that participants’ retention in training and job search processes is strengthened when their prior knowledge is certified, invisible barriers are reduced through support for transportation, care, and digital connectivity, and personal confidence is fostered as a driver of change.

At the same time, early coordination with companies made it possible to co-design relevant training programs, conduct mock interviews, and open up real pathways to employment, facilitating the transition from informal self-employment to more stable occupations with social protection. In total, 82 partnerships were established with public (5%) and private (95%) actors, mainly in the service, commerce, hospitality, and market sectors.

Examples of strategic alliances:

- Breakfast with small and medium-sized enterprises in partnership with Fenalco Atlántico, raising awareness about inclusive employment and the care economy.

- Partnership with Magneto, a digital employment platform in Colombia: 245 participants were contacted by potential employers after improving their job search processes.

- Group interview simulation workshop with Arcos Dorados, successfully connecting young women to McDonald's recruitment processes.

- Arturo Calle and LiliPink became key allies from the clothing and retail sector, where they managed to connect some of the participants.

The intensive use of digital platforms and social media for job searching grew significantly, confirming that digital transformation is now a key requirement for employability. Overall, the program demonstrated that the labor inclusion of women in poverty and with high care burdens requires three indispensable conditions: strategic alliances with the private sector, flexible support systems that eliminate invisible frictions, and public policies that recognize the economic value of both care and informality.

This methodological innovation—graduation with employment, gender, and care—paved the way for more structured and formal jobs, responding to a triple exclusion: gender, economic, and territorial.

What have we achieved?

During 2024, the program impacted 500 women in Cartagena, Santa Marta, and Barranquilla, emblematic territories on the Colombian Caribbean coast where informality and gender inequality mark the labor landscape. With a clear goal of promoting placement in formal jobs, the project went beyond mere labor market insertion: it sought to promote reflection on the transformation of labor market dynamics, recognizing care as a driver of economic and social development.

Throughout the process, a model was consolidated that was capable of breaking down invisible barriers, strengthening alliances between the productive sector and society, and designing contextualized solutions, demonstrating that the inclusion of women in the workforce requires innovation, vision, and collective commitment. This experience generates robust evidence to guide public policies and attract social investors determined to promote productive inclusion with a sustainable impact.

Our Impact

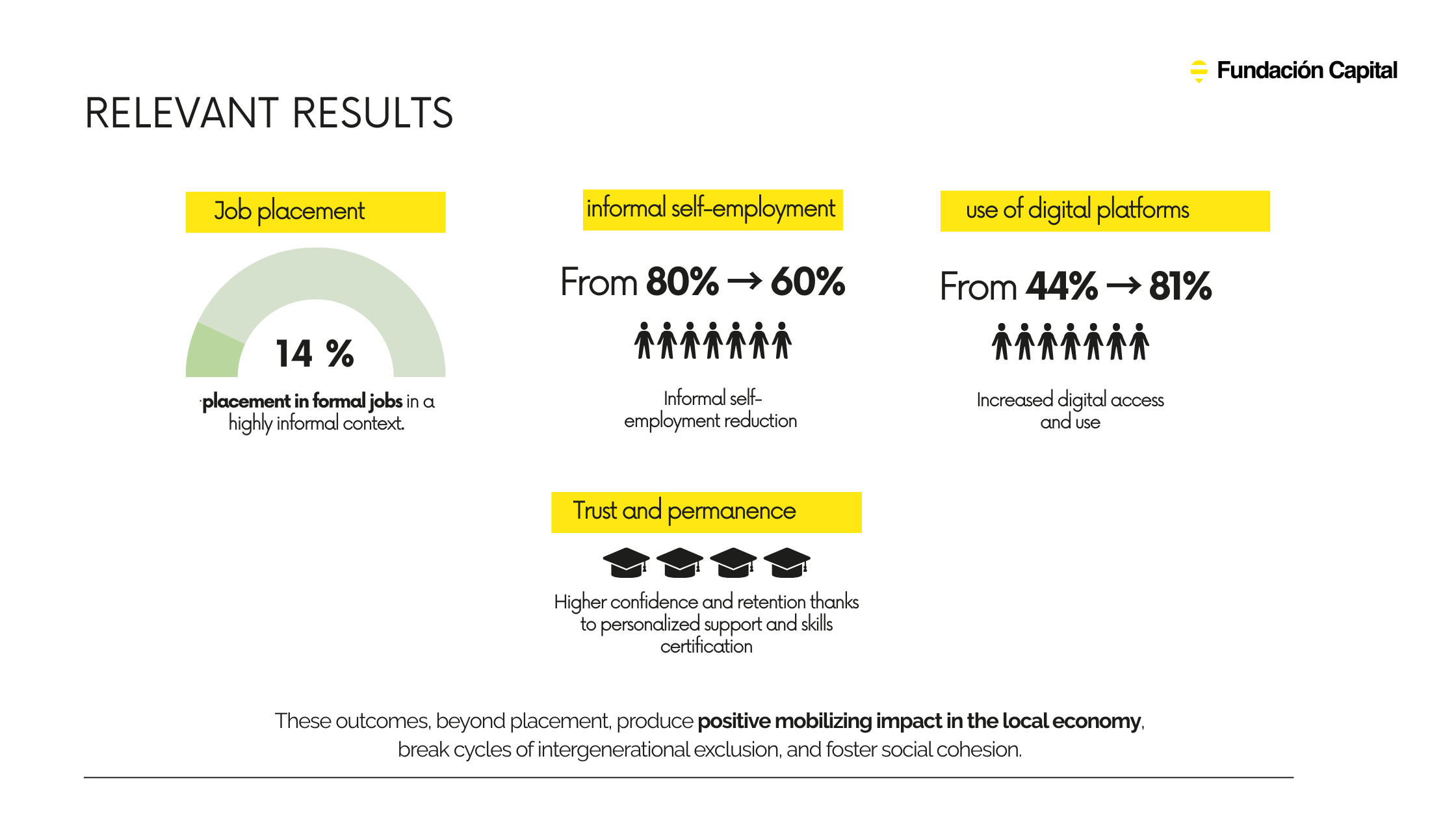

- 14% placement in formal employment within a highly informal context.

- Reducción del autoempleo informal del 80% al 60%.

- Increase in the use of digital platforms from 44% to 81%.

- Greater confidence and retention thanks to personalized support and skills certification.

These results, beyond job placement, have a positive and mobilizing impact on the local economy, break cycles of intergenerational exclusion, and generate social cohesion.

Lessons learned

Importance of a comprehensive approach: The program showed that processes are sustainable when technical, psychosocial, and logistical barriers are addressed simultaneously. The combination of training, emotional support, economic incentives, and personalized accompaniment proved critical to sustaining participation and improving outcomes—an approach that local and national governments can adapt within economic inclusion policies.

Engaging the private sector from the outset: Involving companies from the design phase enabled the co-creation of relevant training, the implementation of interview simulations, and the opening of real job opportunities. Inclusive employment is built through direct dialogue with those who create opportunities: the private sector.

Recognition of pre-existing skills: Many participants already had competencies developed through care work or informal economic activities. Certifying and valuing these skills increased their confidence, strengthened self-esteem, and facilitated connections with employers, demonstrating that talent already exists—it simply requires visibility and recognition. From academia and the private sector, training processes can be promoted to support the labor market integration of this population segment.

Overcoming invisible barriers: Support such as subsidies for care, transportation, and connectivity made a meaningful difference. These elements—often considered “additional costs”—should be understood as essential enabling conditions to ensure equal access to formal employment. This includes integrating community care services into employability programs and replicating models such as Bogotá’s Manzanas del Cuidado, aligned with Decree 533/2024 – Employment for Life.

Digital innovation and the use of AI: Training in digital platforms and the use of artificial intelligence tools significantly increased women’s competitiveness, particularly among young participants. The share of participants using job portals rose from 44% to 81%, and job searches through social media doubled—demonstrating that digitalization is a prerequisite for labor inclusion. This segment holds strong potential for developing flagship programs with the STEEM sector, linking young female talent through rapid cycles of training, practice, and labor market engagement, while the State plays a key role in guaranteeing basic access to connectivity and user-friendly tools for building job profiles and searching for employment.

Financial sustainability and inclusion: Support in financial health and income planning strengthened participants’ stability, encouraging responsible decisions around saving, consumption, and debt. This component helped ensure that formal employment translated into a real and sustainable pathway out of poverty. While the financial sector has made important strides in developing new products for populations in vulnerable situations, integrating a gender lens remains essential to close credit access gaps, promote savings, and facilitate productive investment among women caregivers.

Transformative Social Investment Perspective: Scaling Up the Graduation Approach for Women Caregivers

A key lesson learned from the pilot project on the Caribbean coast

Experience has shown that improving the employability of women living in poverty and with heavy care responsibilities requires going beyond traditional training. Success was achieved by combining training, logistical and psychosocial support, digital innovation, and strategic partnerships with the private sector. This enabled a real transition from informal self-employment to more stable and formal occupations.

This evidence confirms that inclusive employability is not an ancillary service, but rather a strategic pillar of economic and social development.

Recommendations:

Investing in enabling support to strengthen inclusive employability; recognizing the value of personalized support and targeted economic incentives to address needs related to transportation, care, and connectivity will lead to greater retention and effectiveness.

Scaling the transmedia and digital strategy: building a national public platform that integrates training in employability, gender equality, financial health, and care, personalized through machine learning algorithms. This digital ecosystem should be complemented by psychosocial support delivered via WhatsApp and local partnerships that adapt the strategy to each territory.

Building a national network of allied employers: For inclusion to be sustainable, a network of companies that recognize women’s talent in contexts of vulnerability is essential. This involves making fiscal and reputational incentives visible, establishing gender- and care-sensitive hiring protocols, and promoting agreements with chambers of commerce and employment agencies. The private sector is not a guest actor—it is a central partner in this transformation.

Sources:

- Central Bank (2025). New evidence on labor and business informality in Colombia. Essays on Economic Policy, No. 108, February 2025. Bogotá: Central Bank.

- DANE (2024). Care Economy Satellite Account 2021-2023 (technical bulletin). Bogotá: National Administrative Department of Statistics, July 5, 2024.

- Government of Colombia (2024). Decree 0533 of April 29, 2024 (which regulates the incentive for the creation and retention of new formal jobs, “Employment for Life”). Bogotá: Ministry of Labor.

- McKinsey Global Institute (2015). The Power of Parity: How Advancing Women’s Equality Can Add $12 Trillion to Global Growth. McKinsey & Company.

- ILO (2024). Closing the gender gap to boost the economy and productivity in Latin America. Labour Overview in Latin America and the Caribbean 2024 Series. Lima: International Labour Organization.

- OECD (2025). OECD Employment Database – Employment rate by sex (ages 15–64), 2012–2024. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

- ECLAC, Promoting labor inclusion as a way to overcome inequalities and informality in Latin America and the Caribbean, Third Regional Seminar on Social Development [Presentation].

- International Labour Organization. (2018). Care work and care workers: For a future with decent work. Report.

- United Nations Development Programme. (2024, March 8). The missing piece: Valuing women’s unrecognized contribution to the economy.

To learn more about our initiatives, follow us, reach out, and share.